From the late 18th century to the mid 20th century, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Anna Julia Cooper, Virginia Woolf, and Simone de Beauvoir were all having a conversation with another without even knowing it. They were all chiming in on the existence of a phenomenon and concept that had they been in the same room together, they would have realized was the same thing: women’s liberation from a patriarchal society. Despite hailing from various time periods, places, classes, and races, their theories can all be observed as revolving around a single axis issue. For these women, it was evident that women were not free in the same way that men were free to choose what kind of life they wanted. It was clear for these women that they had very little choice and also very little resources to articulate their situations, much less try to find solutions to their problem. However, Gilman, Cooper, Woolf, and de Beauvoir all shed light on what they felt was the dilemma and how they thought it could best be solved. They knew that women must become independent of man, in many senses of the word, and they must also come together if they hope to effect any change in society. Coming together may seem difficult since women do not all share the same backgrounds or identities. That being said, no matter the race, class, or geographic location, due to “anatomy and physiology” (Lemert 2010:346), women all over the world have a shared experience that unites them. It is clear then that with independence comes consciousness, with consciousness comes unity, and with unity comes change.

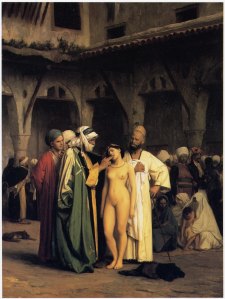

The independence of women, according to de Beauvoir, is one that is unlike any other previous movement in which a group of humans have fight against a system of oppression. De Beauvoir argues that whereas racial groups or class groups have statuses that change due to singular historical events, the status of women has always existed in societies everywhere and cannot be blamed on a war or document. In her view, women are the absolute “other” because in no capacity are they ever the “one.” For instance, a foreign person in one country is considered a native in their country, so although they may have the experience of being seen as the “other” in one place, they still have the opportunity to be the “one” in their home community. Using the language of “one” and “other,” women are always viewed and treated as the “other.” De Beauvoir states, “[Woman] is defined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her; she is the incidental, the inessential as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute – she is the Other” (Lemert 345-346). Women do not have such a space where they can exist without men in the way that men can navigate their daily life focusing on only themselves. An example of men and men’s needs always being a constant, inevitable presence in women’s lives can be seen in Woolf’s fictional, yet very accurate, story of a woman walking and thinking. As the woman, who is supposed to be representative of Woolf herself, walks around pondering the relationship between women and fiction, she suddenly finds her path obstructed by a Beadle. A Beadle is an officer of the church, and in Woolf’s story he is a metaphor for the limitations and guidelines placed onto women by men. Woolf describes the scene: “Instinct rather than reason came to my help. He was a Beadle; I was a woman. Thus was the turf; there was the path. Only the Fellows and Scholars are allowed here; the gravel is the place for me” (Lemert 262). Both Woolf and de Beauvoir identify that a woman is supposed to understand her place in society as existing in relation to men. Gilman understands this relationship in economic terms as well by acknowledging that women are not economically independent from their husbands. Gilman claims that a marriage is supposed to be a partnership where both individuals work just as hard and earn according to the effort they put in, but it is clear that this is not the case. Not only are married women not allowed to work and make money, the work they do at home cleaning, cooking, and taking care of the children is seen as their duty. Supporting the family becomes a married women’s job, but yet, she is not paid for it, and she is also seen as inferior to her husband despite putting in just as much time and effort, if not more, into what she does. Clearly, there are discrepancies across the board between what men and women are allowed to do, but in order to tackle these differences, women must be able to be heard and understood independent of their relationship to men. Instead of talking about women as wives and mothers, we need to be able to comprehend them as women who are able to exist not just as a sexual beings or maternal figures, but rather as a human being with individual hopes, fears, and dreams that have nothing to do with pleasing the opposite sex.

Despite writing from different eras and locations, all four theorists describe the experience of women as if it is a singular, unified experience. Yes, there are nuanced differences amongst all women as they identify with different races, classes, religions, and nations, but one thing is the same that brings all women together. That is, women from all different walks of life at the end of the day share the same anatomical physiological structures that somehow impact the way they are treated at both a micro and macro level. For women of all cultures there is an expectation of their role as mothers and wives, no matter how the rituals of getting to that role differ for every woman. For Cooper, women of color are in a unique position in society. She states, “With all the wrongs and neglects of her past, with all the weakness, the debasement, the moral thralldom of her present, the black woman of to-day stands mute and wondering at the Herculean task devolving upon her” (Lemert 179). In much the same way that Gilman stares at the yellow paper symbolic of her imprisonment, so do women of color stare before the laws and history put before them that continue to keep them silent. At one point Cooper recounts an all too familiar experience in which a white man refers to her as a “girl” simple because of her sex and race. For Gilman, she is also treated like a child because she is literally placed in a nursery as well as ordered around by her husband as if he were the parent and she were the child. She comments on how he gives her medicine and doesn’t allow her to write, as if what she has is a disease when in reality that disease is only real insofar as it affects not only her body but her mind as well; and this disease is called patriarchy (Lemert 173-174). Patriarchy, a society in which men are at the dominant position and women in the subordinate, affects all women negatively. In addition, not only do women have a shared experience, they also have a shared enemy. Men are enemies in that they inhibit the freedoms and capabilities of women. This is not to say that men at their core are evil or that the divide between men and women is one that must be solved through war. Quite the contrary, all four women seek to harness the power that women have of being able to care and have love for others in order to achieve a status in which both men and women are equal.

In all of their contemporary societies, these theorists felt that women were not given a voice or space that was independent of men. The home space consisted of women serving men and boys as wives and mothers while men largely dominated both the work and intellectual spaces. Even though it was clear that there existed inequalities and discrepancies between men and women, for all of the theorists, they felt significant advancements were not being made to change this. Surely not all women wanted to be in such a subordinate and belittling position in society, but then why were they not doing more to disrupt the social stratification and patriarchal structures? De Beauvoir posits, “The reason for this is that women lack concrete means for organizing themselves into a unit which can stand face to face with the correlative unit…They live dispersed among the males through residence, housework, economic condition, and social standing to certain men – fathers or husbands – more firmly than they are to other women” (Lemert 347). Cooper also makes note of this in her writings as she observes how white women treat women of color: without respect and as if they have nothing in common. However, at the end of the day, women must be able to put all those other differences aside if they hope to achieve liberation for women at large. Once all women acknowledge that they have a shared experience, they must use that to shed light on the issue and change it. The economic independence that Gilman dreams of, the social equality that Cooper demands, the academic recognition that Woolf aspires to, and the unified women’s movement towards progress and freedom that de Beauvoir imagines can only be possible if all women speak out against the injustice they have been dealt and altogether work to redress that. Cooper describes a nation as being “the aggregate of its homes” (Lemert 179), so a woman equal in the home also means equality for women at a national, even international level. For this kind of women’s liberation that all four theorists described in some capacity or another, it must be a three-step process. All four theorists so movingly identify the lack of autonomy and mutual respect that women receive from men in society and this acknowledgement of a need for independence is the first step. However, this kind of independence is only personal and so there must next be a shared consciousness that women must all recognize and accept that allows them to realize their affinity for one another. Lastly, once the need for independence and a shared experience is celebrated, women must then come together to actually gain independence for women and continue to honor and recognize all that women have suffered as well as achieved.

It is incredible that over the span of 100 years, all four theorists were describing a very similar situation that is the subordination of women and the perpetuation of a patriarchal society. On the one hand de Beauvoir notes, “[Women] have no past, no history, no religion of their own; and they have no such solidarity of work and interest as that of the proletariat” (Lemert 347). On the other hand, women do have a past, a history, religious values, and most importantly, solidarity even if it is not in regards to race, class, etc. Women have existed just as long as men have and have experienced a long history of oppression by being made to feel as if the only reason women exist is to make men happy never taking in account what makes women happy, or at least not being able to do it because of social norms and in some extreme cases, laws. Despite new forms of feminism and social progress, the issues that these four theorists touch on still exist today. So then, one feels impelled to ask the question, “Why haven’t things changed yet?” And the response to that after having read Gilman, de Beauvoir, Cooper, and Woolf is that things are changing, but it is not change that matters so much as continuity. If women come together once and achieve one goal, the struggle is far from over. To use Woolf’s story, we cannot let that little fish, that revolutionary thought, die. At every turn, both men and women must look out for the gaps and divides, the privileges and limitations, the injustices and the inequalities and be willing to speak out against them. Cooper was right, “To be alive at such an epoch is a privilege, to be a woman then is sublime” (Lemert 184). Altogether independent, women have the power to change history for good.

Reference

Lemert, Charles, Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings, fourth edition, Boulder, Westview Press, 2010.